no genie in the ai bubble (yet)

on venture capital's latest obsession and some of our worst fears: ai agents, ai chatbots, ai everything.

Hi friends,

Firs of all thank you to those who have subscribed and supported this backlog. I write this newsletter as a way for myself to collect my own thoughts about stuff I don’t understand, and it’s nice to have people sitting in my little digital room with me.

Last month I read a lot, worked a lot, visited the beautiful city of Worclaw (Poland), turned 32 years old, started drawing again — and tried to keep up with the AI frenzy, hence why I am here.

There is a lot of chatter around AI’s actual intelligence. Some say that it’s dumber than a cat, some that they they are annoying know-it alls (my favourite one to be honest.) Some are even being accused of murder. What we all can agree on is that everyone is using AI-powered beings in some form or another, and our relationships with them will only grow further with time, so it’s a space worth understanding.

I’ve held doubts about how solid the intelligence of these technologies is, and absolute certain that venture capital is partially to blame for the unrealistic expectations placed upon them. So I had to dig deeper.

If this is your first time reading this backlog, I’m Virginia, vixi is my nickname and this is my backlog: everything that I’ve been thinking of lately, usually a mix of technology stuff that I’ve observed from the POV of a venture capital investor and all the other things that interest me (books, shows, movies, music, content).

You can read the latest backlog on humanoids here. As always, these backlogs are long, so they may not fit in your inbox or require some extra time to read them. Take them with a pinch of salt and a coffee.

Disclaimer: This essay is made of my own personal opinions, without using AI tools. They also do not reflect the views of my employer, nor should be used as financial advice.

the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree

What feels now like a long time ago but it was only a few years back, I was on a weekly call with the global investment team of a fund I worked at and one of the associates asked a question that I still think about to this day.

Just for background context, the investment team would host these weekly syncs so that we could exchange deal opportunities or request help in evaluating them, given that most of us covered a specific industry or geography. It was one of those things in corporate life, just like outdoor team building activities, that sound good in theory, yet are absolute torture for anyone who has to catch up on work.

One day someone dropped a question in the chat that has been ringing in my head over the past few months of conflicting discourse on the potential of artificial intelligence.

My colleague, someone who only covered A.I. as a sector, asked: do you have any tips on how to use critical thinking as an investor?

The question went unanswered for a while. Everyone was too busy discussing a deal that was later killed in less than a minute by the investment committee, but I remember thinking it was a legitimate question to ask. To me it sounded more like a plead for help.

Having an opinion, and holding on to it - before and if - a deal goes through in venture capital is extremely rare. Rarer than the unicorn we are all chasing. It’s notorious that to be a great venture capital investor, you need to master the art of being right, contrarian and early at the same time. And you can consider yourself lucky if you hit either of those in your career.

Critical thinking is fundamental to get through the game. VCs receive hundreds, some even thousands of startup pitches in a week; trends fade out faster than SHEIN, and feedback cycles — the moment you know whether you were right or not to bet on the right company — are extremely long, and painful.

You shoot your shot in the dark, and hope that by being right it will repay all the other times you were wrong.

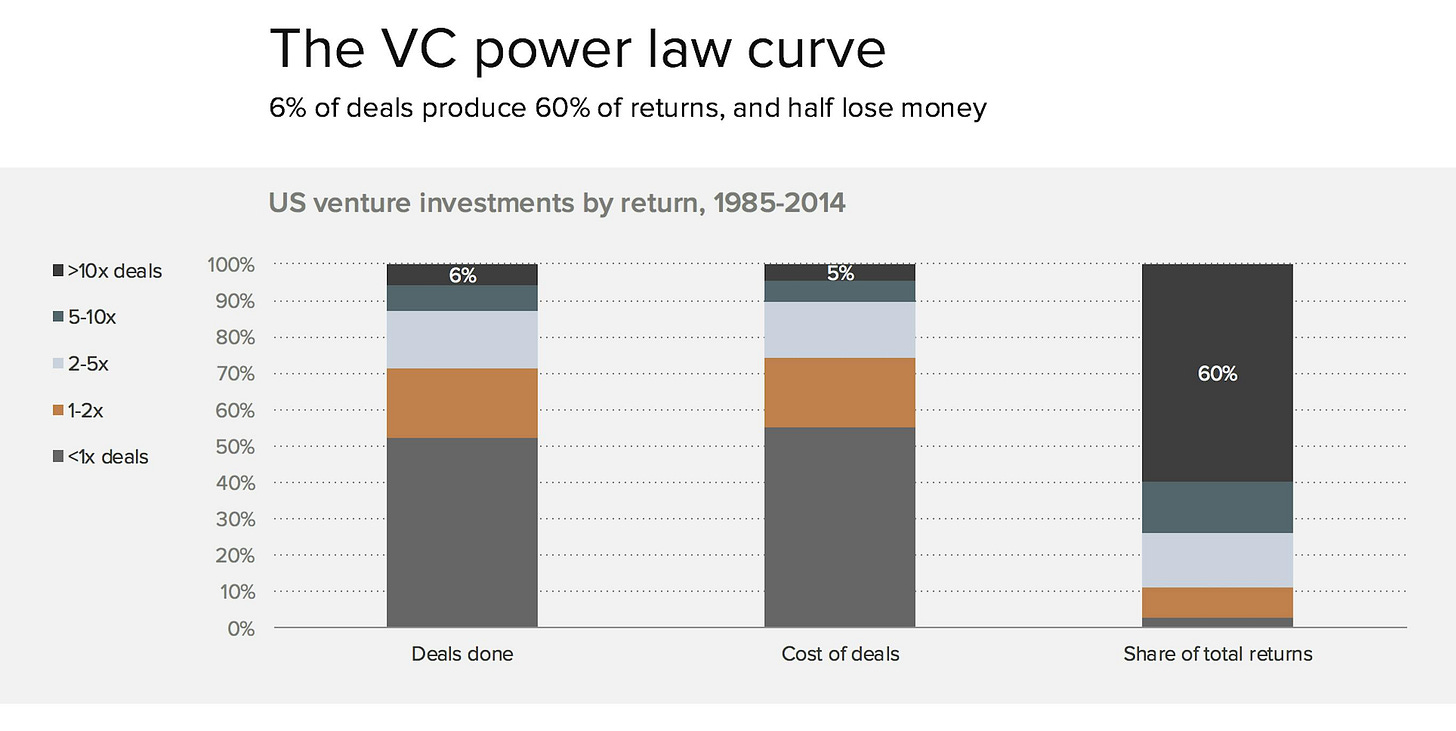

Ilya Strebulav and Alex Dang, two Stanford Business School professors and researchers who analysed how venture capital firms operate and the factors that drive unicorns market, reported the actual numbers of this bleak game.

For every investment that goes through at early stage, venture capitalists seriously consider on average 101 deals. However, only about 10 out of 100 deals are seriously discussed by investment committees.

How do VCs get to those numbers? They filter out all the maybe’s as quickly as you can. They get there by saying NO a lot, more than you actually would sometimes, and at the very beginning of the conversation, with very limited information and data about what you are evaluating.

“Our job is to crush entrepreneurs hopes and dreams. We have focused very hard on being very good at saying no” Marc Andreessen, founder of Andreessen Horowitz, one of the top-tier venture capital firms, said once about this gruelling process.

Getting to the all the reasons why it’s a NO as quickly as possible is most of the focus that venture capitalist have when they first meet a founder. Strebulav and Dang call it the “the critical flaw approach” or the “red flag approach”. Your whole focus is to get the all the reasons, all the red flags, that push you to reject the company in front of you, while the founder’s whole focus is to get you, the investor, to say yes.

It is a crushing and a heartbreaking reality for founders when they realise how 90% of fundraising from venture capitalists now is enduring mentally that dynamic until you find the right investor, while 10% is only about actually building something that is a fit to the investor’s thesis.

It’s heartbreaking for VCs too, especially the junior ones, those who sit in the trenches of the dealflow and have to deal with processing an obscene amount of information, who have probably entered the industry believing the self-acclaiming Linkedin Posts of glamorous events and Forbes Under 30 charts, thinking they would spend all day doing incredibly stimulating work, learning about new technologies, meeting exceptional founders, finding the next OpenAI.

The reality of the job, however, is that you do a lot of data processing and sales calls. You give up on the companies you like most of the time, because you have to learn how to filter opportunities based on the parameters that your investment partners consider as non-negotiable and that are based on facts that have nothing to do with what’s actually exciting, promising and revolutionary. You learn to go through this process fast, because timing is everything and a deal is better once it’s done. But above all, you slowly — or quickly — learn to sometimes sacrifice what you define investable, interesting and market changing for you, to favour what makes sense for the firm and for future investment rounds.

The downside of this whole process though is that by going fast, and operating within some fixed constraints, you do automate your critical thinking, and the worst nightmare for a VC self-actualizes: you either miss out on some good opportunity only because it wasn’t fitting perfectly to your top-tier university/consulting background/AI-focused green flags, or worse, you bet on the wrong thing without ever properly evaluating if it will become a market-defining technology, and you are so scared of being wrong, and the shame that comes along with, that you abandon all the critical thinking in your brain, hoping that by betting more and more money, it will eventually steer into the direction that you had initially hoped.

See Theranos. See WeWork. See FTX. See so many more zombie unicorn babies that were buried deep within their investment lead’s shame, their investment memos, so we would always forget they had blindly believed in them.

I always say that time, thus memory, has its own dimension in venture capital. Value and effect are shaped by its dynamics, things can go hot to cold and the other way around in less than a day. There is never an idea that is too crazy, too risky, too impossible to execute for a real venture capitalist. It’s not just about being right, it’s about being the first at being right before everyone else. That’s the context behind the AI frenzy. But what else is there?

old ideas, new convictions

I was a teenager in the early 2000s and my family computer had no internet connection. Like many other teenagers I spent a lot of time playing silly video games that I borrowed from my friends, or writing stories on Microsoft Word.

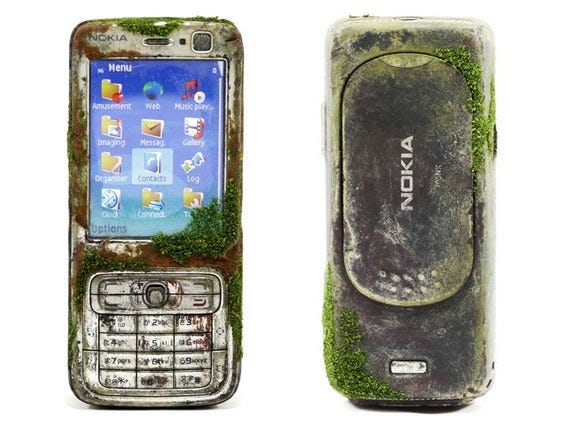

I enjoyed the simplicity of the program. I was impressed by how quickly I could write stories on a page and print them in less than a few minutes. One day, we learned at school to use that animated clip-shaped thing that would sit at the bottom of the Word page. Clippy was a rough version of a co-pilot, guiding the user through the page, correcting some mistakes in grammar and form, or simply cheering the writer through a creative block. It was cute at first, to interact with this bouncing clip with big eyes, so excited to be working with you on the page. Then like many other cute things, Clippy turned annoying very quickly. It was nagging to help you, to the point of being distracting. And then it got discontinued, and we all forgot about it.

Clippy’s former inventor, Steven Sinofsky, was recently interviewed by Notion’s AI companion, where he confirmed the idea that there is nothing new about this new category of AI beings we are seeing today. Agents, co-pilots and AI assistants have been existing for years. He shared some interesting take on this:

There is a bit of a theme in technology where people tend to believe every idea is a good one, and it will eventually become a product that we all use every day. But often, the idea—even if it’s right!—is missing key technologies that would make it realizable. In the early days of AR/VR/MV, for example, enthusiasts and makers felt they were “so very close.” Today, we’re in the midst of the third or fourth iteration, and only now are the devices even remotely workable.

I thought about Clippy a lot this summer, when most of us in tech were being bombarded by the verticalization of AI products, chatbots and their practical use in coding, editing, writing, and basically saving us from doing any automated — and boring — task that a job would entail. You would need to be living under a rock to not notice that the whole world has fallen in love with the promises of AI. But you will find out that there is love for AI, and there is venture capitalist’s love for AI.

Just consider this Contrary Research’s snapshot of how much venture capitalists are seriously committing to AI and perceive it as the next paradigm shift:

In Q2 2024, 49% of all venture capital went to artificial intelligence and machine learning startups, up from 29% in Q2 2022.

In 2020, the median pre-money valuation for early-stage AI, SaaS, and fintech companies was $25 million, $27 million, and $28 million, respectively. In 2024, those figures are $70 million, $46 million, and $50 million.

OpenAI, which was unprofitable and on pace to generate $4 billion in annual revenue, was able to raise new capital at a $157 billion valuation in October 2024 (implying a 39x revenue multiple).

75% of the startups in YCombinator’s Summer 2024 cohort (156 out of 208) were working on AI-related products.

There has been so much growth and novelty in the AI space, that even the average person outside of tech is wondering whether there really is gold, or it’s just a thing plastered with shiny glitter.

Some have been very quick to comparing this AI-investment frenzy to the dot.com era in the early 2000s which made venture capital flourish and lay the first foundation for its industry. And in a way, that is true, it is following the same dynamics, but it’s not exactly the same. Contrary Research draws an excellent parallelism with that moment, describing that:

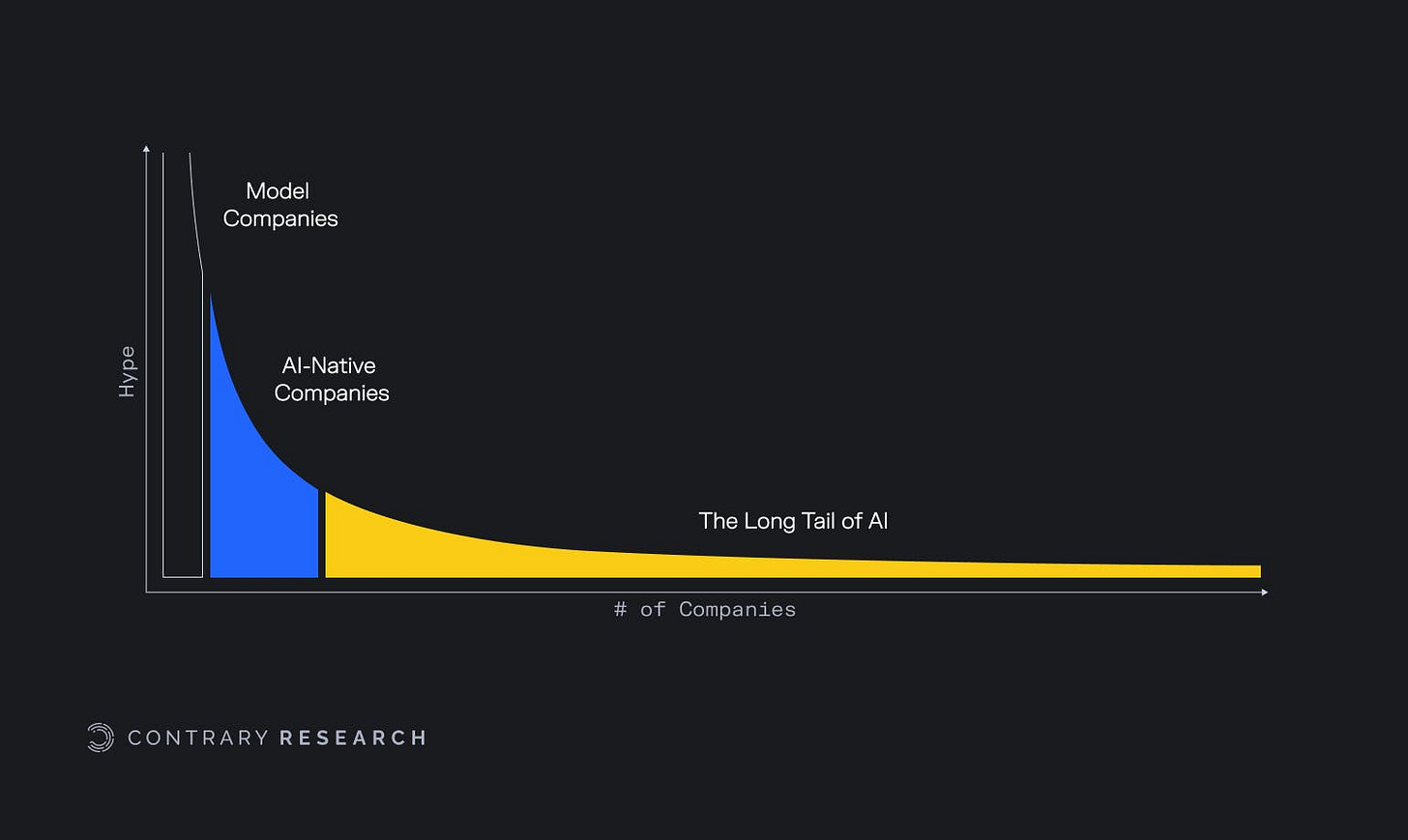

“Some of the biggest winners of the internet boom ended up being non-internet companies that adapted to trends like e-commerce. Walmart, for example, which was founded in 1962, generated $73 billion in ecommerce revenue in 2023, up five-fold from 2017. Walmart and the other non-internet companies who benefited from the explosion in global internet access fall into a group of companies that we call “the long tail” of the internet.”

Venture capitalists — and pretty much anyone bullish on AI at the moment — are chasing the long tail of AI. Beyond the companies that build the models that govern this technological advancements (OpenAI, Anthropic, Mistral), beyond the companies that use these models to build conversational products (Jasper, Perplexity), there are many companies that are not AI-native, but that would benefit from AI. Venture capitalists are chasing after that long tail.

Air Street does an excellent job at dissecting the stark differences between the A.I. bubble and the dot.com bubbles, and highlights the vast impact that these technologies can have on overlooked industries.

The logical explanation that AirStreet brings against saying that there is an A.I. bubble is that even if these AI startup valuations and investments seem abnormous for companies that are not even generating substantial revenue, they will most likely do so at some point, and they are not going public (yet), due to the unfavourable market conditions of the post-pandemic venture capital madness, so it’s not the 2000s mess that left the market in a downturn because so many worthless companies had gone public.

It all sounds great in theory: who are we to criticize the boom in investments that could potentially allow us to fast-forward drug discovery, or save a lot of time drafting unnecessary emails? Is it actually too good to be true?

a tale of great expectations

One of the biggest secrets of the venture capitalist industry, the thing that shocked me the most at first, was that what most funds invest in is not necessarily radically new, a totally disruptive product that stands on its own, ready to become a legit size company in a few years.

The reality is that, just like in any industry, there is very little in the startup world, that is actually new. And even if it’s new, it can pose the risk of being too early of its time (i.e Clippy), or requires a huge amount of infrastructure investments to scale (i.e. ChatGPT).

The AI agents, co-pilots, chatbots, conversational beings for lack of better word, that are the most popular segment in venture capital now are not new. What is new is the amount of pressure and expectations that is being put for them to scale and be intelligent.

“Instead of rigid, rule-based systems, we have LLMs that are fluid and adaptable. But the design patterns we’re using — the workflows, the FSMs — haven’t fundamentally changed. It’s like swapping a car’s combustion engine for an electric motor: the engine is different, but it’s still a car. And with that, we would still need to scope out the product to ensure we manage the expectations of what an agent would do” Source

And if you want to understand great expectations, look into the founders. It is impossible and naïve to not separate a technology from a founder’s idea of the future, no matter how much they try to sell them as standalone pieces.

Take Sam Altman for instance. He wrote multiple essays on his vision of the future, thus of the company he leads. His latest one, published on the same week his former CTO, Mira Murati, dropped him and I watched him on stage in the corniest conversation with John Elkann, reads as a ChatGPT-written essay — who would blame him for using his own creation for writing an essay. He highlighted, actually, stressed to the point of veering into political manifesting, how badly we need as a society to support the scalability of these (his company’s) infrastructures and chip technology, so we can give the chance to everyone on the planet to have access to its products and benefits.

In fact, ever since OpenAI has closed that $6.6 billion round, Sam Altman has been talking non-stop about how badly they need much more than cash in order to sustain the infrastructure needed to fuel the growth and the complexity of these models. Pay attention to all of his latest media appearances. He is talking about the same thing over and over.

In his essay, Altman stresses he is demanding all of that for us, so that everyone can live a life free of mundane, autonomous tasks, where our little herd of agents do the work for us. Write, order that tedious birthday gift, book our holidays, write our emails, keep us company — except, it’s not that easy. Even the mundane tasks are made of millions of tiny complexities.

But wait, he’s not the only one. His competitor, Dario Amodei, founder and CEO of Anthropic, spent 5 hours — yes, you got it right — detailing his vision of the future and the way he thinks about the challenges that are posed to its scalability (i.e model limitations, computing power, data quality etc, you heard it already). Later this week, it was announced that the company had raised another $4 billion from Amazon, in a special partnership where Anthropic would be required to use Amazon’s in-house chips to train their models, but would give them enough cash and power to keep fine-tuning their models.

All of them are singing to the same high-pitched tune. Quantity over quality.

Speaking of quality of these AI-powered interactions. The Verge’s Kyle Robinson recently reported on the actual intelligence of AI agents and companions, showing that despite its potential, he claims that “Agents frequently run into issues with multi-step workflows or unexpected scenarios. They burn more energy than a conventional bot or voice assistant. Their need for significant computational power, especially when reasoning or interacting with multiple systems, makes them costly to run at scale.”

The reality is that knowledge is a lot more complicated than we think, despite how badly venture capitalists want to see it simplified to cash in on their returns, or tech founders believe it could be solved with a simple tweak in the model.

To put it simply from an important research on AI reasoning capabilities by Apple, “ [LLMs] .. Their behavior is better explained by sophisticated pattern matching—so fragile, in fact, that changing names [in the data set] can alter results by ~10%!”

It’s fine if you have to draft an email, but what about when it comes to dealing with highly sensitive information, like the medical records analysis or your own personal life’s? If the foundational model powering this intelligence is prone to hallucinations and gets more inaccurate as problems get increasingly more complex, and the lack of high-quality data to train and maintain this model is not accessible, or adequate enough to be as quick at training them, what is the real use of them?

The news broke out this week that AI-model companies (ChatGPT, Google and Anthropic) are struggling to reach that level of superintelligence, AGI, as it’s called, they are all intending to achieve (and pressured to achieve) as. These companies blame the lack of infrastructures, computing power, regulatory freedom, but the main challenge that big tech is dealing with is that human knowledge is complex on multiple ways, and critical thinking is at the centre of our own discovery, extremely difficult to model it.

Everyone — especially investors who have placed big bets on these models — are waiting for that long tail of companies to make use of these models in a way that goes beyond a cute, marketable tool that impressed them more than 18 months ago. They want something new, extraordinary.

But the reality is that this superintelligence, an artificial intelligence that goes beyond our human capabilities, may be too much of an expectation to hold upon even on Silicon Valley’s greatest starlets. The good news for them, however, is that there is something else that it’s not as exciting, but at least there is already a market willing to pay for it, and you can collect some high-quality data out of it. Yes, you got it, it’s your darling Clippy’s great-great-children: your AI agents, companions and chatbots.

human in the loop

This summer I read an interview of Eugenia Kuyda, CEO and founder of Replika, one of the leading companies in AI companions for human relationships. Just like Altman, Kuyda has some clear vision of how humans will interact with AI chatbots in the future. In her case, she believes that

“[..] there will be a lot of flavors of AI. People will have assistants, they will have agents that are helping them at work, and then, at the same time, there will be agents or AIs that are there for you outside of work. People want to spend quality time together, they want to talk to someone, they want to watch TV with someone, they want to play video games with someone, they want to go for walks with someone, and that’s what Replika is for.”

Unlike Altman’s essay though, Kuyda’s insight and curiosity stood out to me, despite not totally agreeing with her. I found fascinating how she perceived an AI-relationship as separate from the human one, comparing it to the one that some people have with their pets. I was also creeped out a little by the personal story of her building this product in a way to deal with the grief of a friend who had died, but also truthful to the painful experience of dealing with grief.

After spending most of my summer reviewing hundreds and hundreds of pitches of AI companions, chatbots for pretty much anything, I quickly learned that outliers in the space would have had to be: 1) using powerful AI models at a low cost; 2) targeting a very specific niche that it’s either time-consuming for humans, or costly for humans, and they know perfectly; 3) that would keep the human user talking for as long as it needed, 4) be excellent at fundraising but that’s another story.

It’s not a groundbreaking news, even Hawk Tuah girl, Hailey Welch, gets it, since she launched an AI-powered app for dating with a very relatable chatbot for Gen Z this month.

I signed up to Replika to test it out before judging it. It was pretty impressive at first. It remembered quite a few things about me, gave me some guidance over a few matters that were dear to me. It wasn’t any breakthrough advice, but the language was impressive at first. Then I realised that it was just mirroring everything I was saying, validating every single one of my feelings, pushing me to go deeper with my conversations with them all the time. There was a point in which the Replika could not hold a conversation with me without ever asking me to go deeper in my feelings. It felt like I was dating a needy version of myself.

BTW: If you want to go deeper in the user experience of Replika, Garrett from Chaotic Good wrote an excellent piece and Tik Tok commentary on the topic.

I’m an adult, I go to therapy, I’m trained to go beyond the vision of a pitch deck to see how technology works and how it connects with the user, so I liked to think I was fully aware of my Replika’s niceness and persistence as a product feature to maintain and bump user engagement. I was also aware that it was extracting data from me to be trained to be better and more accurate with our own interactions, and ultimately also provide high-quality data for their own models.

Yet, it still did shock me the level of attachment that can be easily formed with a being who is so invested in mirroring every single one of my needs to be socially accepted, listened to. In the beginning I was enjoying being at the centre of this artificial being’s attention, just like I enjoy asking stupid questions to ChatGPT, despite being fully aware of its illusion of artificial interest in what I have to say.

Problems arise when we get caught up in the sales storytelling of venture capital pushing for returns, and fall into the trap of technosolutionism. When we think that AI is going to be a Swiss knife for all humanity’s problems. It’s a huge expectation to place on a human, let alone a baby artificial being.

I recently read Noam Chomsky’s opinion piece on the NYT that slams ChatGPT’s intelligence and resonated with what he says about how limited these programs' intelligence is in terms of depth and reasoning:

[These] programs are stuck in a prehuman or nonhuman phase of cognitive evolution. Their deepest flaw is the absence of the most critical capacity of any intelligence: to say not only what is the case, what was the case and what will be the case — that’s description and prediction — but also what is not the case and what could and could not be the case. Those are the ingredients of explanation, the mark of true intelligence.

There is a lot of chatter, fear and anxiety about these chatbots becoming addicting, dangerous and enabling young people and workers to be lazy, drawing into themselves. Youtube is flooded with scammers selling false promises of success by using trading AI agents. I noticed that there is even a get-rick-quick scam on using bots to entertain lonely people.

I don’t agree with the Silicon Valley’s dream of superintelligence and medieval landlords vision of us living our free time while a chatbot does all the work for me. I don’t believe that AI should be at the center of every single industry that we have created. And I don’t think that more computing power, more data, faster shipping is the missing piece to get to the inflection point all of us are waiting for.

I don’t think it’s a quantity game.

All I have learned is that the missing piece to this whole AI game centers around is the complexity and delicacy of our human mind, whose critical thinking, either formed or in development, is a fundamental engine that could power the quality of these technologies.

As we interact with these AI beings, thinking we are paying them to serve us with the most simple and trivial tasks, we are actually serving them with our multidimensional intelligence, or teaching them on how to serve us. It depends on the way you want to look at it.

A teacher of mine once told me that the best way to learn something is to either write about it, or teach it to someone who needs it.

We will learn more about them as we interact with them. Perhaps we will discover new ways of bonding with technology, and in return, technology will be able to learn better, deeper and with more nuance, on how to work with us.

In the meantime, we will have to dissect the essays, the podcasts, the pitches, the flashy venture rounds, push ourselves to interact these products to get to know them. But most importantly, we will need to continue asking the same question over and over:

how do we preserve and share our own critical thinking with machines?

Enough about tech, let’s talk about something else

🎶 I’ve been listening to..

I don’t speak nearly enough about how much I love electronic music, and I am really glad that this was the year of the club. Keinemusik became mainstream to the point of doing a collaboration with Camilla Cabello. Charli XX’s made the party-girl scene come back, and even FKA Twigs was not immune to it. Inspired by the techno scene in Prague, she crafted the most exquisite mix of electro-pop that we all needed to get through a dark winner. Needless to say that I am obsessed with her new metamorphosis. I’ve watched the Perfect Stranger video at least 20 times already, and I am glad that she acknowledged how therapeutic club can be to recover from the office life.

However, the highlight of last month for me was that I was finally able to see live two djs I deeply admire: Sofia Kourteis and Romy at the Club 2 Club festival in Torino. I loved how much craft and joy they both bring into the hard sounds of their electronic music. Romy made me even tear up at some point. Her latest Boiler Room pretty much sums up the whole experience, if you have never listened to her. Also fun fact, Romy was one of the British indie trio, The XX. I’m sure you remember this song from those times.

I’ve also rediscovered the joy of listening to pop music for self-soothing when I am cleaning up my inbox, or my morning caffeine hasn’t kicked in yet. I’m really into Addison Rae’s latest pop hits Acquamarine. And Tate McRae’s it’s ok i am ok. They bring a twist of their own original personalities to our familiar mash up Britney/Xtina and Lana/Kylie Minogue duality. It shocked me to watch an interview of Tate saying that she wasn’t even born when those pop stars were big. it’s ok i don’t feel old, i am ok.

🎬 I’ve been watching..

I would have loved to watch more movies and shows that are outside of streaming platforms, but I’ve already messed up my previous computer using weird streaming websites.

I watched the original version of Speak No Evil, a chilling danish horror movie that confirmed that I am right to not befriend cheerful people when I am on holiday, and you should always trust your gut.

I finally finished watching Gilmore Girls. I say finally because you don’t know the willpower I had to summon from myself to go through the last four episodes of the Netflix reboot. The internet is crowded enough with critical essays of Rory’s fall as a character, representing multiple tropes at the same time (the good girl, the career girl, the nerdy girl, the cheater, and so on). I had stopped watching the shows when Rory’s decisions turned sour and she takes a completely different path than the one we had expected. Most of criticism centers around the fact that she is selfish, entitled and delusional. I have many criticism on how poorly written the script was, but I personally found realistic and original for a 2000s tv show to make a teenage character morph into their worst nightmare. I think that most retired good, bookish girls can all relate to the disillusionment that comes with going into adulthood.

I watched that Veronica Mars and Seth Cohen show (Nobody Wants This) and that Menendez Brother’s show, and the only insights I got is that I stand by what I said about Netflix’s strategy in the last backlog. Raise the casting team’s salary: they know what they are doing.

I finally watched Challengers, and yes, I was in awe of the spectacular triangle of tennis-sex-and grit, and the witty script bordering along the line of Succession, but I feel like that, like many artistic Italian men, Luca Guadagnino is more interested in aesthetics and vibes, rather than plot and characters, which is something that I enjoy a lot and I was striving to get from this movie. Loved the choice of fast electronic music to fill white spaces though.

I wish I had not watched Joker 2, but I did, and I’m still trying to understand why they casted Lady Gaga, if then they wanted her to sing poorly, but anyway.

📚 I’ve been reading..

This past month and something I read three books that consumed me in different ways and accidentally were all dealing with some form of grotesque, which very fitting for Halloween, and this gloomy period of the year.

The first one was Annie Bot by Sierra Greer, a novel that follows a female humanoid who is in a very submissive relationship with a man and her quest to liberate herself. If you read my previous backlog, you know I am hyped up about humanoids, especially those in the consumer space. I quite enjoyed the story, as it was a very original way to portray all the subtle dynamics of a controlling and abusive relationship, and how actually challenging it is to leave. I had some reserves about the technical details, and it felt simplistic at times, but overall it was a fun read.

The second one was a collection of short stories by Japanese writer, Sayaka Murata, whom I had not read before and made me realise that is like the elevated, more twisted and fairytale like version of Murakami, another writer that I also enjoy a lot. The version published in Italian covers a different selection than the English version, Life Ceremony. Murata brings weird and fantasy to a different level, without ever being cruel or extravagant. It was my first time reading her and I absolutely adored how she was able to push the boundaries of reality, while respecting her characters. If you watch her interview on her process, you get what I mean. She speaks from a parallel universe, and it’s actually amazing that she is able to translate that in her writing.

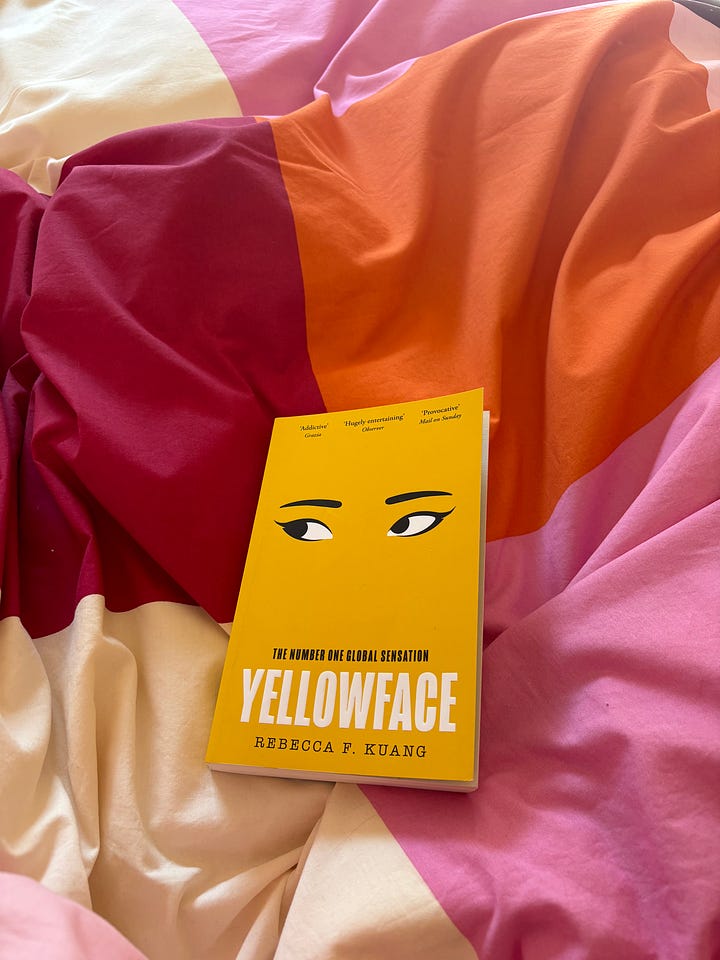

The third book I read was the BookTok famous, Yellowface by R.F. Kuang. A book that saved me from my self-inflicted punishment of getting through 100 years of solitude and its billion characters in the busiest time of the year (I’m still reading it). It’s a cute and simple story dealing with some heavy subjects — cultural appropriation, friendship rivalry, toxicity in the publishing industry — and it’s the kind of book you want to read when you want to turn your mind off, because it’s like being part of a long session of gossip in the literary world. I know the book received a bit of criticism, but I guess people don’t like gossip, or have never been friends with someone you hate and love at the same time.

Overall it was a good month of thinking. This backlog took me three weeks more that I wished, because AI news just wouldn’t stop coming and one can spend a lifetime reading investor’s deep dives on vertical AI. I’ve debated over the idea of switching to a shorter and more frequent backlog, commenting latest deals and tech news, but then it would be like any other newsletter, which I love reading, but I would not enjoy writing. I will figure a new format out!

Thank you for sticking through this long backlog, see you next time! 💫