implementation details, humanoids and tech delusions.

PSA: Please stop making humanoids that look like the Rubber Man from American Horror Story.

Hello, friends!

This is my first and, hopefully not the last, dispatch of a my backlog. A real brain dump of what I have been thinking of lately.

I think about robots a lot, so you will read about them in the future, but lately I’ve been thinking about humanoids particularly.

P.S. Substack is warning me that this post is too long for your inbox, but I trust you will open your favourite browser or Substack app to dig into it. 💌

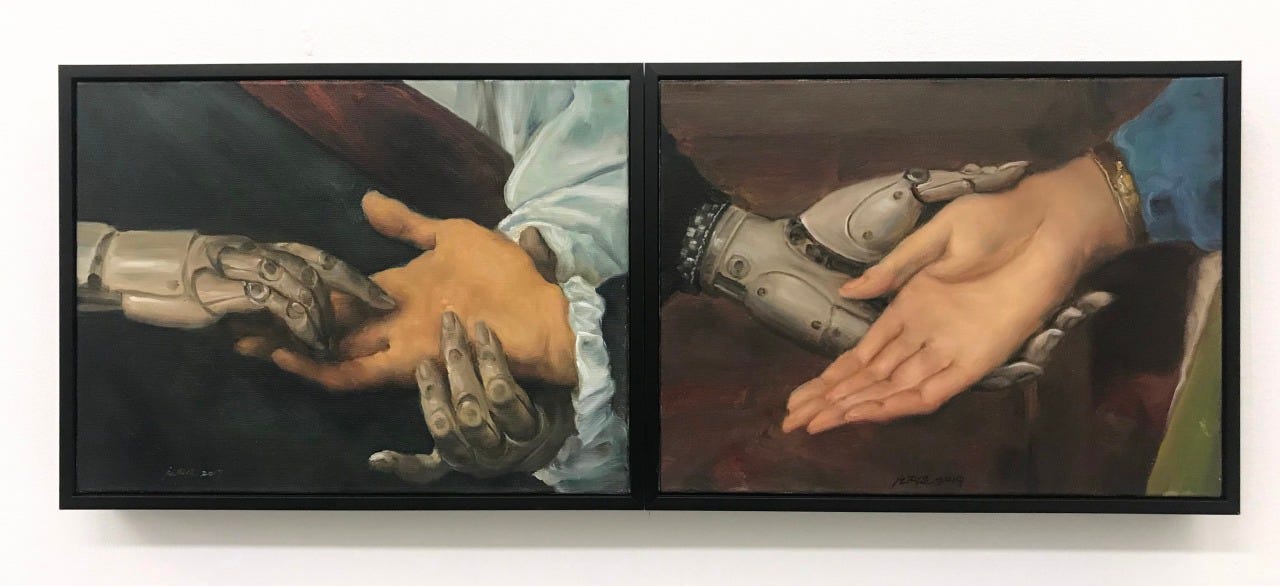

Last week I was obsessed with this tell-all story about Google’s attempt at giving AI a robotic body. Or if one looks at it the opposite way, to make robots a bit smarter than we think. Experienced tech leader and current leader of the Everyday Robots project, Hans Peter Brondmo, was hired by Google in 2016 to accelerate the company’s efforts in the field of robotics. I love this piece because it’s a candid, yet romantic essay on the endless possibilities of human-robot interactions. It addresses the obvious —that we are still far from achieving completely autonomous robots integrated in our everyday life and that venture capital’s allergy towards hard-tech could possibly be responsible of that — but most importantly it brings robots under a light that Donna Haraway with her Cyborg Manifesto has been reiterating for many many years. That as machines —robots in this instance — strive to imitate us in order to integrate with us, we in turn are subjected to the same transformation and merge into the machines we use.

Our pop culture has vastly been focusing much more on the extreme ends of this tension: see Ex Machina, Terminator, Black Mirror, that J.Lo’s movie on Netflix that I couldn’t go past 2 minutes not even for research. On the other end of the spectrum, we don’t even have to dig into pop culture that much, given that the company that is most likely to bring some significant change to the robotics industry was inspired by a movie in which the main character falls in love with an A.I. companion.

There is so much more depth and range into the relationship that human beings have with machines, especially when it comes to robotics in a working and intimate environment, that I am increasingly surprised that all we are left so far are still the same Balenciaga-esque, creepy humanoids that pick up dirty coffee cups on two wobbly, sturdy legs.

And speaking of legs, there is an exquisite section in the article on Hans and his team debating on the assumption that robotics living amongst humans should require standing on two legs.

“The fact is, robot legs are mechanically and electronically very complex. They don’t move very fast. They’re prone to making the robot unstable. They’re also not very power-efficient compared to wheels. These days, when I see companies attempting to make humanoid robots—robots that try to closely mimic human form and function—I wonder if it is a failure of imagination. There are so many designs to explore that complement humans. Why torture ourselves reaching for mimicry? At Everyday Robots, we tried to make the morphology of the robot as simple as possible—because the sooner robots can perform real-world tasks, the faster we can gather valuable data. Vincent’s comment reminded us that we needed to focus on the hardest, most impactful problems first.”

When I read that article I obviously thought of the latest stars in humanoids that got all the robotics bros in frenzy this year. I must admit I was one of those bros.

As an investor, I’m bullish on humanoids. Most of them remind me of the creepy Rubber Man of American Horror Story (pictured above), however, I’m convinced that they will play a significant role in pushing human-machine interaction (also known as HMI) forward, given that they bring to light how complex it is to integrate machines amongst humans, both on a technological and behavioural level. And the technological part is insanely difficult to achieve.

Take the BMW’s two-week pilot with Figure’s humanoids on a production line in its South Carolina plant. This pilot brought a lot of chatter similar to what the Boston Dynamics’ parkour and dancing robot did to people every year. People went absolutely nuts about machines replacing humans, but very little focus was put on achieving the impressive feat of keeping a humanoid standing on two legs. This is what Google’s Larry Page calls in the article “Implementation Details”

Just to use Figure’s latest humanoid as an example, it charges 50% more efficiently than its previous model; its cables have been tucked underneath its chassis, and it is equipped with 6 more cameras and supercharged with an OpenAI partnership that should make the bot hyperaware of its environment, and perhaps able to compute much faster its inputs. Not to mention the $675M that Figure raised this year at a $2.6B valuation that is powering — and pressuring — the robotics company into commercialising its bipeds assistants before everyone else. (See Tesla’s Octopus, Agility Robotics‘ Digit, Apptronik‘s Apollo at GXO Logistics and many more. China per example is going all in on humanoids)

The race to the best humanoid is definitely on, but not for the things we think. It’s a race for who is smarter and (more frugal) at implementing these details.

Another example of this came earlier this year, when Boston Dynamics unveiled that it was powering its popular Atlas humanoid with electric motors, and retiring the old version that everyone came to know with its parkour-like flips and dancing moves.

It was a pretty big deal.

“Hydraulic robots use a series of pistons and fluid to manipulate the limbs on a robot, while electric versions use electrical energy to move and rotate the parts of the robot directly. As such, the switch from hydraulics to electric has big implications in terms of production costs, design and performance.

Electric motors are generally less expensive, less complex, quieter and lighter than hydraulic versions, but they may wear out more quickly, and are generally not as strong as the latter.”

The path towards commercialisation for humanoids is still steep, especially when we introduce them in our private spaces. (See Roomba’s story).

All you need to be convinced how truly difficult it is to make robots move amongst humans in a safe and dynamic way, is to read this blogpost on Motor Physics by Eric Jang, VP of AI at 1X Technologies.

And it’s not just about movements, more efficient charging and hand-gripping, a huge implementation detail on humanoids is actually training them to coexist amongst humans. Another one is getting access to a sizeable amount of high-quality data to teach them to live around us.

I do, however, think that the hardest trick to pull, and the most fundamental of all in scaling hardware technologies, is to simulate simplicity and functionality.

A practical example of that is shown on this article from the New York Times that explained how robotaxis notoriously known to be self-driven and autonomous, are actually aided by companies like Zoox (an Amazon’s company), whose human workers support and train the vehicles in overcoming unpredictable paths or simply assisting them.

“For years, companies avoided mentioning the remote assistance provided to their self-driving cars. The illusion of complete autonomy helped to draw attention to their technology and encourage venture capitalists to invest the billions of dollars needed to build increasingly effective autonomous vehicles.”

The fact that humans train machines should not come as a surprise. Neither should be that fact that venture capitalists get lured into the illusion that a machine is inherently advanced without taking context of the humans who train and build such machines.

It’s a bit old news for those of us who are plugged into the AI-circus for work, however, if you do want to go a bit deeper on the dark side of this topic, Shoshana Zuboff wrote an excellent book that thoroughly explains how our chronic addiction to sharing our life online for free (this is a very important point) powers a moneymaking machine that needs to be constantly oiled by bare minimum wage remote workers. The all-knowing and all-seeing algorithms are just a magical trick.

It reminded me of the story of Hans, the Clever Horse. Hans was a horse that lived in the 19th century believed to be clever because it performed successfully mathematical and logical tasks. The horse was a darling and obedient animal to his owner, a mathematical professor, but it was no clever. Its ability to consciously or unconsciously translate subtle cues from its owners, who guided him towards the right answers, allowed to sustain this simple illusion.

There is a really good chapter about this story on Kate Crawford’s brilliant book, Atlas of AI, which goes super deep into this illusion — even into the source of the metals and raw materials that power the kind of complex systems you need for advanced artificial intelligence. You can check out the map that she and Vladan Joler worked on and blow your mind off how much more complicated this whole ordeal is (note: it was done pre-ChatGPT frenzy.)

There are many turns that this conversation could take: we could talk about how humans can be easily deceived and exploited by interacting with these technologies. Or we could talk about how this type of technological progress could free us from repetitive and mundane tasks, and if the cost of doing that is potty-training my personal Rubber Man Robot, then so be it. It’s all for the sake of a more progressive future, right?

I do agree with Hans Brondmo that it is a bit of a failure of imagination when we concentrate all of our focus in building machines that imitate a narrow version of us. However, it is in this making of the perfect illusion that I believe that we might figure things out about our own humanity that will surprise us, and of course, scare us in some ways.

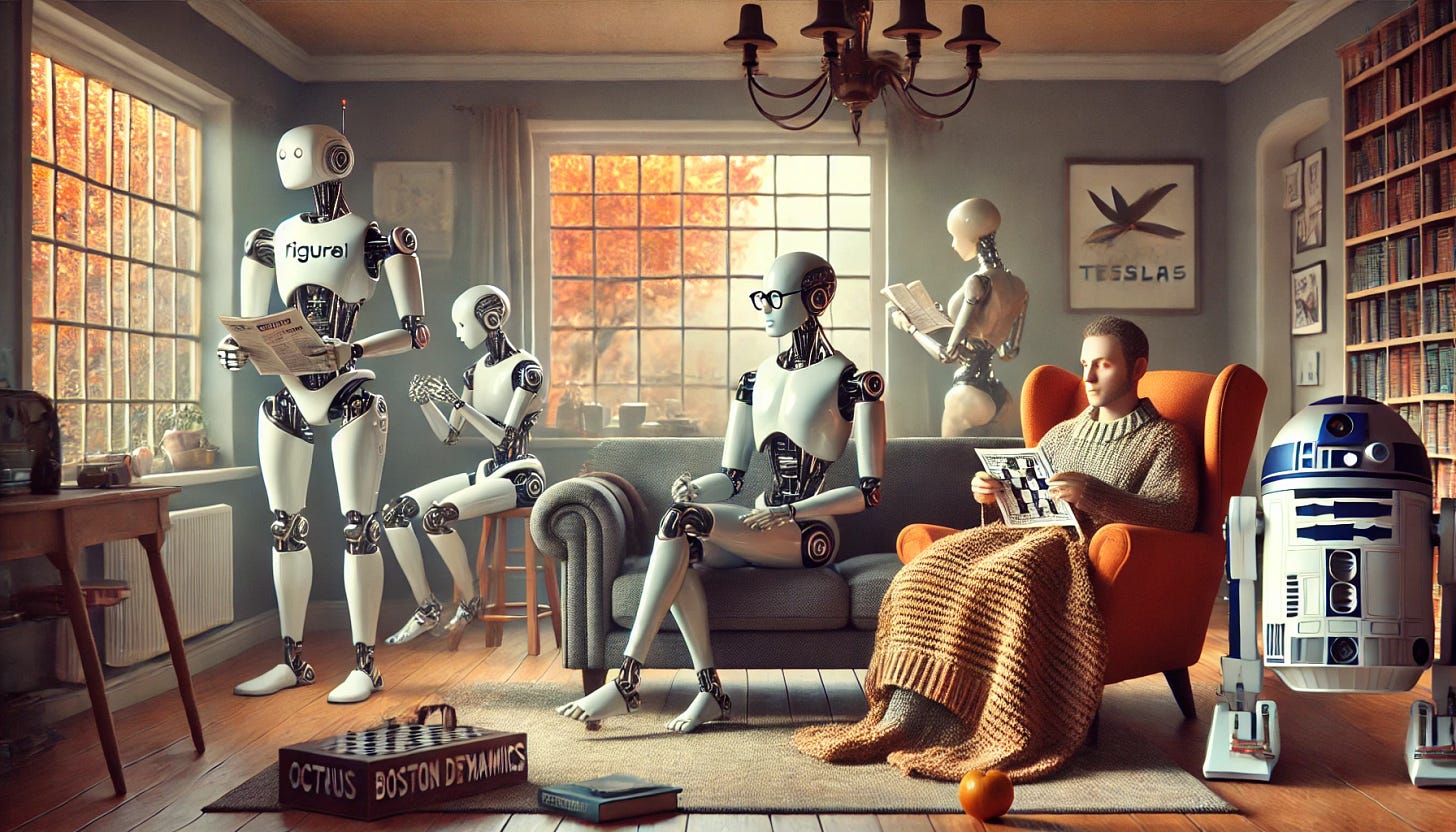

In the meantime, I thought this comment under the video of Boston Dynamics retiring its famous Atlas was really funny and I used Dall-E to imagine a scene of robots having a little break. (P.S. Dall-E was very diligent and precise the first time, and then decided to throw in a human and the Star Wars robot and an apple in the next one.)

Other things I have been thinking about but had no space to talk about it in this piece:

Apple is exploring robotics after failing at its self-driven car technolgy (Bloomberg)

Are we in an AI bubble? Casey Newton answers everyone’s favorite question. (Platformer)

Post-mortem of a deep tech startup that raised $100M in 2022. (Latitude Media)

Why the new OpenAI model is truly astonishing, but it still can’t arrange a wedding seating chart on its own.

The next big thing will start out looking like a toy by A16’s partner

Enough about tech, let’s talk about other stuff:

🎬 I’ve been watching..

I finally watched Tár. I would describe it as the demure version of Whiplash, with a spectacular Prada-esque Cate Blanchett. The ending is just phenomenal, but directors really need to stop producing movies that are over 2 hours unless they are insanely good, because we simply don’t have that attention span anymore. (I’m joking, I would literally watch a 3-hour long corporate training video if Cate stars in it.)

I’m a big fan of horror movies and it’s been a while since I’ve watched a perfect one. The Deliverance was interesting, but mostly because of Glenn Close’s mob-wife aesthetic and foul language; I don’t know if we can consider Baby Ruby a horror movie, but the incessant crying of the baby and the smothering mother-in-law made it seem like one; and last but not least, I watched Smile, which reminded me a lot of “It Follows”, a horror movie that I loved a lot. Smile was a bit predictable, but boy I am still haunted by the smile and I am generally a sucker for a demon tale.

I finally finished the Umbrella Academy series, which had started so brilliantly and flopped so miserably, but I’m a recovering My Chemical Romance fan, so I had to at least finish it. I watched the latest crime series, “The Perfect Couple” only for Nicole Kidman and her algid, robotic face (I love her in The Perfect Wife), and it was mostly okay, except it got me even more convinced of Netflix’s movie production strategy: find two series that worked well (in this case White Lotus and Nine Perfect Strangers), copy the basic principle behind it, hire two talented actors (Dakota Fanning, Nicole Kidman) and save money on the script and dialogue, because nobody will pay attention while they binge-watch through the series to find out who the killer is. The last time I watched Dakota Fanning in a movie, she was a child in Uptown Girls. I love an evil, bratty pregnant woman in a movie, and Dakota pulls it off perfectly. The rest was just background noise for cleaning up my inbox.

📚 I’ve been reading..

I finally went back to reading more fiction these past few weeks, although I did read “The Venture Mindset”, which gave me a lot of behind-the-scenes intel on deals that made venture capital famous. It stopped being interesting when I realised that it was a guide for corporate innovation departments turning into venture capital, which honestly, I think every corporate is trying do, but very few do it well because executives don’t let the poor innovation managers do what they are supposed to do, but that’s none of my business 🤷🏽♀️

I devoured two debut novels a few weeks ago that were both on complicated father-daughter relationships. One is Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh. I loved Ottessa’s short-stories and sad girl novel (sorry), A Year of Rest and Relaxation, but Eileen is really something else. It captures how grotesque and magic puberty is on the body, and it was a very fun read. The other book I read is Tangerinn by Emanuela Ancehoum, an Italian-Maroccan writer who wrote an incredible story on what it means to leave home, to leave Italy specifically; to reconcile two worlds and two cultures, and to lose a father and the story buried within him. It’s unfortunately only available in Italian as of now, but I’m sure it will be translated at some point, because it’s honestly one of the best debut novels I’ve read in a long time.

I also tried to read Zadie Smith’s “The Fraud” because I loved all her works up to Swing Time, but then ever since the pandemic I absolutely cannot understand what Zadie is talking about in her fiction novels or what is going on in the plot. It made me think about that James Wood’s controversial essay that coined that Zadie Smith’s style as hysterical realism. I felt a bit guilty that I finally understood what he was talking about, even though I think that there were other words that could have been used without being a sexist prick.

I would like to end this backlog by sharing a song that I’ve been listening to non-stop while writing this and really captures how I feel when I get to talk, work, think about the things that I love the most (robots, books, books, robots).

Omg this is wonderful!!!! and the Dall.e image of robots having a break is chef’s kiss. So glad i found it